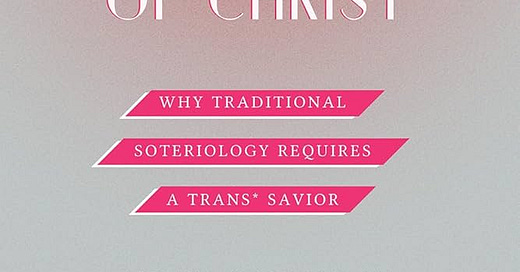

This week I received the first prints of my new book, The Disappearance of Eve and the Gender of Adam: Why Traditional Soteriology Requires a Trans* Savior. It is available for purchase, and first prints go to the public on April 15th. In honor of this (for me) momentous occasion, I am sharing one bit from the introduction below, a short section on what it is to do theology. I reject the idea that theology is the repetition of ideas from infallible sources. Rather, I conceive it as participation in an ongoing dialogue.

...

Christian theology is an ongoing conversation among people divided by time and culture, but united by the conversation itself. In this conversation, the contemporary theologian receives from the past. But even if the theologian tried only to repeat what had come before, they would inevitably contribute some of themselves. In this conversation, there are more and less stable themes, questions, and conclusions. There is, doubtless, a kerygma without which the conversation would cease to be Christian theology. The constructive theology in this book, for instance, presupposes Nicene orthodoxy. But there is also a liveliness and openness to novelty as the theologian attempts to make sense of the world through the conversation.

Scripture does not stand outside this conversation. Rather, it represents some of the first contributors to the dialogue. Today, these contributors are designated by their names, letters (J, E, P, and D) and pseudonyms (Matthew and Mark, Isaiah two and three). Many are lost to history. Each has placed their mark on the exchange, often leaving dialogical friction in their wake. Genesis 1 is in tension with Genesis 2 and 3. Chronicles rehearses and reinterprets Kings, at times quite liberally. In intra-Biblical interpretation, the text did not simply dictate to the reader. The interpreter was an active participant in picking, choosing, contesting, correcting, and reinterpreting. They contributed meanings which, over generations, came to layer the text.

In this process, the most recent interlocutor was never free of the text. Earlier authors imposed some boundaries which could not be crossed. The final editors of the Pentateuch did not feel qualified to harmonize all the divergent versions of ancient stories, nor could they reconcile themselves with rejecting one or the other narrative, even if they were apparently contradictory. But they never merely maintained what had come before. Even in offering the most conservative restatement of ancient stories in new contexts, the interpreter became a new author of the text. Biblical theology has always been dialogical theology.

This has not always been recognized within Christianity. Following the Jewish tradition of the previous three hundred years, most early Christians posited a kind of univocality to scripture. Origen, the early Church theologian, taught that the scripture was uniformly authored by the Holy Spirit. This doctrine, however, did not stop Christians from continued participation in dialogue which drew upon, contributed to, and directed the growing tradition. It opened spaces in which the dialogue continued. “God’s intended” meaning for the text could go beyond, and in quite different directions from the meaning intended by historical authors. Through allegory, typology, and moral readings of the text, Christians continued to both receive from the tradition and to donate their own voices to the growing cacophony.

As Christianity perdured, the dialogue enlarged, branched out, and diverged. Even, or perhaps especially when theologians thought of themselves as repeating earlier themes, they contributed innovative additions to the conversation. Where Paul claimed that “sin entered the world through one man … with the result that (ἐφ’ ᾧ) all have sinned,” (Rom. 5:12) Augustine could extend the claim that it was Adam “in whom (in quo)” all have sin.7 Where Paul was concerned with “works of the law (ἔργων νόμου)” (Gal. 2:16), i.e. circumcision, dietary laws, and sabbath obedience, Martin Luther could read concern about “works righteousness”, i.e. a belief that one could achieve righteousness independent of God.8 Much of the dialogical nature of this work remained hidden, certainly from the public, but also often from the interpreters themselves. Christianity maintained both connection across the tradition and dialogical flexibility to articulate doctrine in new and helpful, or even provocative, ways.

In the aftermath of the Reformation this approach to the Bible became more difficult to uphold. The increased pressure on the text to sort out disagreements (a task once left primarily to the institutional Church), the need for a meaning accessible to a more general public, and the development of modern hermeneutics, often influenced by scientific constructions of literalism, led to significant shifts in what was possible when approaching the text. More important than any other development, however, modernity (and even more postmodernity) brought an appreciation of historicism – the extent to which original authors and their intentions are necessarily culturally distanced from contemporary readers.

Today, it is impossible to read scripture in the same ways that pre-modern Christians did. But this hardly requires an end to theology as dialogue with the scripture and tradition. Indeed, it allows the dialogical nature of theology to be more self-conscious and explicit. It further requires that we recognize the Biblical authors as some among the many partners that join us in the long tradition of Christian theology. Self-critical Christians must take seriously their own role as dialogue partners with the Biblical text and the following tradition. As Kathryn Tanner writes: when doing theology, one must accept that one is in “a constructive dialogue and intellectual contest with all those other Christians, past and present, who have been similarly concerned …” For present purposes, we can expand this statement to include those many Jewish contributors without whom the Christian tradition would never have come to be.

Looking forward to the release!